(Click the images for higher resolution versions!)

Down by the water, a little café had an array of weird, wonderful stained glass windows. Whole sections of them had come down, lying smashed on the floor, and the kitchen was a burnt-out disaster area. Our guide told us about taking the Top Gear crew around for an episode filmed here: the final cut made it look like an escapade of devil-may-care banter, but offscreen they’d come with a motorcade of NBC-sealed caravans and a BBC health & safety man with a clipboard, and spent every second off-camera wearing breath masks they burned each night. A few irradiated wrecks sit in the shallows, and in asking after them we finally found out why the huge cranes we’d seen before were serving a lake: the entire inlet had once been part of the River Pripyat, but had been blocked off to avoid contaminating the river (which feeds into the Dniepr, and thus flows directly through Kyiv.) Heading back up to the cafe, H.R. suddenly started shrieking in my jacket pocket. I remembered a story Nikolai had told us about a visitor who suddenly became so strongly radioactive that he went off the scale of the first three Geiger counters they used, and they had to bring in several more powerful counters just to isolate where on the increasingly upset man the problem was. It turned out to be a tiny fleck of graphite which had stuck to his boot. I was glad when I got past the hotspot and H.R. calmed down a bit.

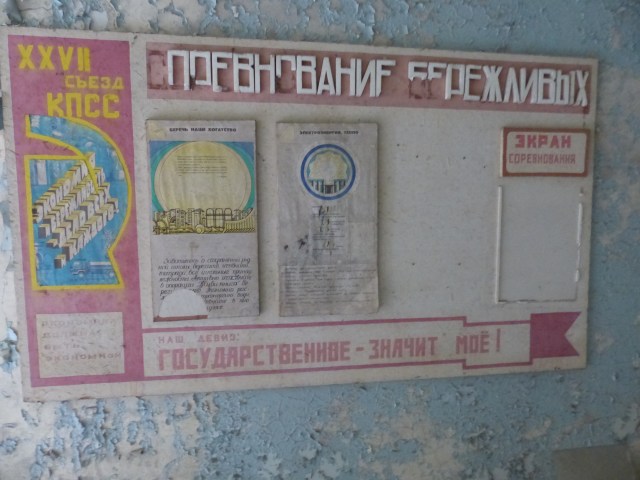

Visiting one of the schools was a wonderful experience; a huge heap of children’s gas masks in the main hall distracted everyone who was only interested in getting the most ~poignant~ photo, leaving the rest of it free and full of interesting relics: textbooks full of poetry and puzzles, posters of Russian poets and maps of the Socialist Republics educating the children of Pripyat on topics that were once geography, politics and science but are all now merely history. Given free rein for an hour, Tom, Bill, Matt and I aimed for an interesting Art Deco-looking factory adjacent to the school and almost immediately got lost in the slightly radioactive undergrowth. We found it in the end, and got a thrill of genuine exploration, with no sign anyone had been there in a very long time: undisturbed little fried-egg stalagmites, an unbroken fluorescent tube that imploded like a rifle shot under someone’s boot and made us all jump, corridors so dark we needed phone lights to proceed. Exploring it felt a lot like videogame pathing, with passages blocked by fallen air ducts forcing us round more interesting routes, but we finally found the Thirties-style glazed section on the roof. Once we were done taking pictures with the wrecked neon signs that crowded the rooftop, the route back down was a very easy staircase of dusty luxcrete and leprous peeled paint.

The rest of the day passed far too quickly: the dry, graffiti-slathered swimming pool, where the peeling surfaces and missing ladder of the diving board didn’t dissuade damnfool Englishmen from climbing to the top; plastic circles from lane barriers were heaped up in the rotting changing rooms. The post office, with beautiful murals inside and out: an abstract wind goddess realised in ceramics on the exterior, and inside a painting of The Post through the ages, from Egyptian scribes right up to CCCP cosmonauts, who looked out across a mail room full of broken glass, empty phonebooths and telegram forms. The prison, hardly used in affluent, law-abiding Pripyat, but with big serious cells and hefty reinforced doors just in case. The fire station – tower, sadly, inaccessible – and motor pool, full of vehicles and engines that had been wrecked to stop looters, some dumped up on the roof with cranes that had themselves been smashed up. The overgrown athletics track, with its bleachers now thoroughly bleached and rotting, and a rickety floodlight structure I quickly gave up on climbing. It was another beautiful day, the vegetation bright and green, puffy white clouds against a clear blue sky, and it was a genuine shame to leave.

Back in the town of Chernobyl itself, a display of the robots and other machines used in the cleanup sit behind a fence and an array of radiation warning signs: part museum, part memorial. Nearby stands an actual memorial to the firefighters and cleanup workers, in a chunky, emotive style; Bill noted our guide, who had been completely cheerful and nonchalant throughout the tour, was actually visibly moved by this part (which didn’t stop half the group from striking poses in front of it). Another monument, glimpsed only from the bus, consists of a pair of origami cranes sat on stone plinths, and a spray of metal pipes that might be bamboo, might be control rods; a gift from the Japanese, who have their own relationship with the atom.

In the centre of town is a terrible angel made of black-painted rebar, blowing its trumpet above a long row of black and white signs. The signs are mostly adorned with flowers; the names are in Cyrillic, and look for a moment like the names of the dead, but there’s a concrete map of the whole Zone next to them, strewn with metal markers, and you realise that the signs are road signs; the monuments are not to people, but lost villages, dead and buried in the poisoned earth.

Kyiv & Chernobyl 2015

Kyiv monasteries & Mother Motherland – Maidan, St. Michael’s & St Andrew’s– Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant – Palace of Culture –

Duga array & Pripyat Hospital – City of Pripyat & Chernobyl monuments