(Click the images for full-sized versions!)

Water sprayers were about on the streets of Vake as we left, damping down the dust and making the air deliciously cool. We rode the Metro to Didube station, across the river from something marked DIGHOMI MASSIVE on our maps, and decamped into a chaos of numberless minibuses. Getting the right marshrutka was as simple as making eye contact with one of the blokes at the metro station. “Marshrutka? Batumi?” “Akhaltsikhe please.” “Akhaltsikhe! Follow. Here.” “How much?” (Ten fingers.) “When will this go?” “When ready.” With the bus mostly empty, we figured we weren’t in a great rush, and it was equally easy to find some cheap pastries in among the market-stalls there (through the time-honoured tradition of pointing at random appetising-looking ones).

The drive was almost half the width of the country – two hundred whole kilometres! – and followed the banks of the great butternut-coloured Kura River up through yellow plains and green dales into the dry ochre highlands of the south-west. The combination of creaky marshrutka, mountain switchbacks and roads that hadn’t seen a great deal of love since Brezhnev made the ride slightly hair-raising (though not as bad as Kalamata to Mystras), and only halfway through did I notice one of our fellow travellers had a bird in a very small box on her lap. We arrived early in the afternoon, by an anonymous obelisk to the dead of 1941-45, and made our way to our guesthouse. Akhaltsikhe is a charismatic town of no great size, nestled in a confluence of valleys; its name, one of those gorgeous, quintessentially Georgian-sounding words, means “New castle.”

We had found rooms at the “Happy Holiday” guesthouse (linked ‘cos it’s very highly recommended). The room was clean and well furnished; the host couple spoke little English but their 12-year-old daughter was a splendid translator, and the stickers on the door forbade us from smoking cigarettes, e-cigarettes, and hookah. We showered so we wouldn’t be Akhaltsticky, had a splendid lunch round the corner, and then headed up to the new castle.

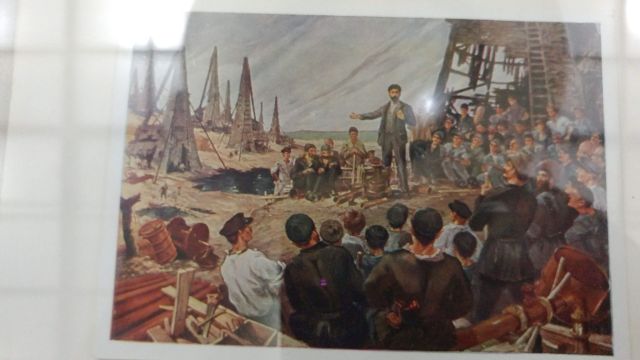

The huge Rabati castle is a monument to a local military history so long, bloody and tangled I don’t have the time or confidence to attempt to reproduce it; the present form changed hands repeatedly between the local Georgians, Tamerlane’s Timurids and the warring Islamic gunpowder-empires that succeded them, notably the Persian Safavids and the Ottoman Turks. A recent, clearly very expensive, reconstruction has decided to return it to a specifically Ottoman splendour of carved wooden shutters, shady colonnades and tinkling fountains, all under prominent Georgian flags.

The reconstruction – I specifically use that rather than restoration – is at once gorgeously accomplished and weirdly soulless. There’s no furniture and little information, and none of the buildings give any real clues as to their purpose; the rebuilt madrasa, its stonecarving perfect, was just a line of empty cells. There’s not much of a museum-y aspect to it; this is history as monument-to-marvel-at (and very marvellous it is, too), with no attempt to present it as having ever housed something alive. (The available information was also oddly eager to point out that it was in no way a working mosque.)

By pure chance, we’d arrived on June 30, the day of the martyrdom of Saint Shalva of Akhaltsikhe,* now commemorated every year by a big town music festival – Georgian-flag bunting was going up, drinks being unpacked, sound systems unlimbered. We wandered back down the hill at dusk, and chilled on the terrace outside the guesthouse where the landlord, in reasonable German, offered us some of his homemade wine and, through his daughter, helped us plan the next leg to Batumi. It emerged that something that looked entirely logical on the map – the direct road through the mountains from Akhaltsikhe to Batumi, which was most of the reason we’d even ended up there – was too poor quality for anyone to want to drive us there. Given the quality of road Georgians happily would deal with, we were both slightly frightened of what that might look like. So getting to the Black Sea would mean looping all the way back to Kutaisi, at considerably greater time and expense than expected. Ho hum.

Arpi had a stomach complaint and retired to bed early, but the daughter of the house and a group of her school friends showed up, ready to go up to the castle for the festival. They all practiced their English on me – it’s very striking how the older generation speak Russian as a second language and the younger ones English – and I showed them some British coins, explaining the queen, the lion, the portcullis, the flowers. Our hosts saw nothing untoward about letting a group of preteen girls wander off with a large foreigner, so they took me up into the towers of Rabati (unlit, poorly paved, wobbly ladders, general Ukrainian-tier health and safety but with scorpions – all genuinely great fun) and we watched the open-air concert** unfold in Georgian, Russian and accented English, the crowds of happy Georgian teenagers in the thousand-year-old fortress feeling at once incongruous and perfectly appropriate.

* Shalva Toreli-Akhaltiskheli was a 13th century general serving in the armies of Tamar, who trashed various Turkic and Azeri armies and was executed by the last Shah of the Khwarezmian Empire for refusing to convert to Islam. This was plenty to get you sainted at the time – things were different back then. Or perhaps not.

** Finishing this post up at the dawn of 2020, I wondered if there was a video of the festival from 2018 anywhere online. There isn’t, but there is one of the 2017 episode, which featured – utterly charmingly – guests from Newcastle-upon-Tyne.

Good morning, Kutaisi! – Museums and wine – Chiatura from above – Pioneers’ Palace, Gori – Tbilisi – David Gareja – Akhaltsikhe – Vardzia