We started the grey, rainy second day with another Nick Kembel recommendation, a breakfast place called Ding Yuan Soy Milk, very popular with Japanese tourists. We ate xiaolongbao (little dumplings full of broth, not a million miles from khinkali), fried chive pockets, hot bowls of soy milk (Fran’s sweet, mine savoury with croutons and a slight cottage cheesy texture), and a clay-oven sesame bun. We picked up our train tickets for later at a convenience shop, in a ritual which will be fine the second time but was awkward the first (you enter your details in a kiosk thing which then gives you a receipt that you then take to the till and print tickets…?) This was a different district, a little quieter and more businesslike than Ximending, with gloomy passages through buildings and staircases promising abandoned underground shopping areas, and random shops with excellent names: Mikhail, THREEGUN, Master Max, Murder Gentle.

The first stop of a fairly busy day was the Nanmen (South Gate – the gate character 門 is really easy to remember, it looks like saloon doors) branch of the National History Museum, part of an old Japanese-occupation era camphor and opium factory. Camphor, extracted from trees, was a massive, incredibly lucrative export from Taiwan in the late 19th and early 20th centuries: as well as its role in traditional medicine and mothballs, it was an essential ingredient of nitrocellulose, itself an essential component of celluloid film (which revolutionised cinema), smokeless powder (which revolutionised warfare), and, less successfully, those billiard balls that kept exploding. Camphor’s value, its exploitation and the resulting brutal struggles between indigenous Taiwanese, Chinese settlers, and Japanese masters were dealt with matter-of-factly; the impression it gives is the Japanese weren’t particularly better or worse for the locals than the Qing Chinese, Germans or British who came before them or the Nationalists who came after (more on that in a moment). Natural camphor extraction peaked in the 1930s, outcompeted by synthetic alternatives, and the factory was shut down in the sixties.

The opium section was equally matter-of-fact, with a lot of the issues around heroin addiction basically the same then as now: it described Japanese rulers struggling to balance strict prohibition of a substance regarded as evil and morally corrosive against the huge revenues from taxing legalised drugs; and whether cutting addicts off or providing them safe controlled access was more inhumane (and socially disruptive). A video screen showed an old man had a singing a Hakka folk song, in tone and topic basically a blues song about life ruined by drugs. Upstairs was a special exhibition on plastic waste, climate change and other crises of the Anthropocene – it was all good stuff but plainly aimed at school groups and familiar content (we have ecological catastrophes at home) so we skipped through it and enjoyed the old brick-and-stone buildings in the dripping rain.

I got turned around a bit and instead of the Sun Yat-Sen museum* ended up at the 228 Museum, named for the uprising of Feb 28 1947. This was in another Japanese-era building (a very handsome old 1930s thing) holding a small, harrowing museum. After the Japanese surrendered at the end of WW2, ending their five-decade occupation, Chiang Kai-Shek’s KMT took control of Taiwan and inflicted the same inept, hateful horrorshow of corruption and mismanagement that eventually saw them kicked out of the mainland (…and so fleeing to Taiwan) a few years later. Locals protesting against this were violently crushed by the KMT, with tens of thousands tortured and murdered and forty years of White Terror and martial law. Most of this only came out in the 1980s with the end of martial law. It’s an excellent, important museum which told us more about Taiwanese national identity and its roots (the Japanese influence – 75% of the population being able to speak it, regardless of ethnicity, before the war – was really news to me) than anything else so far, and had many – very current! – points around censorship and social control, a very clear implicit point of difference with the mainland.

Next was going to be the National Museum, but the nice lady manning the front desk instead pointed us at the Crafts Institute across the road, an absolutely incredible modern pagoda full of contemporary Taiwanese art. Downstairs was devoted to the woodcarvings of Chi-Tsun Chen, a mix of charming old bits of Chinese mythology and local allegorical scenes (some feeling like a sort of modern Socialist Realism), probably the most memorable being a little boy carved to look as if he was squished against a glass window. Upstairs was a range of works by other local artists in wood, paint, ceramic and metal, all local and mostly breathtaking. I admit a reflexive prejudice against Contemporary Art museums because so many of them are filled with low-effort Rothko toss or pointlessly gross transgression but this was impressive and beautiful.

We only had a couple of hours available to see the National Museum of History (more of an art-history museum, really) and catch our train, so were slightly relieved to learn that it was mid-refurb and only two floors were open. The top floor was about money, which interested me a lot as (without actually knowing if this was true or why), the historic Chinese approach to coinage seemed quite different to the European one (ie: given amounts of precious metal, with value based on the intrinsic worth of that metal, stamped with a government symbol as a guarantee of size and purity). Chinese coinage seems to have been generally treated as recognised trade tokens rather than intrinsically valuable (replacing shells used for the same purpose), cast from baser metals. The square-in-circle design of traditional cash coins has symbolic elements but practically also means they can be hooked on to cords or bamboo for large transactions; coincidentally it also means they’re harder to use for leader’s portraits as pieces of government propaganda. That was the hook, as well as knife money, ghost-face money, silver ingots, and various Chinese-zodiac-themed banknotes from around the world.

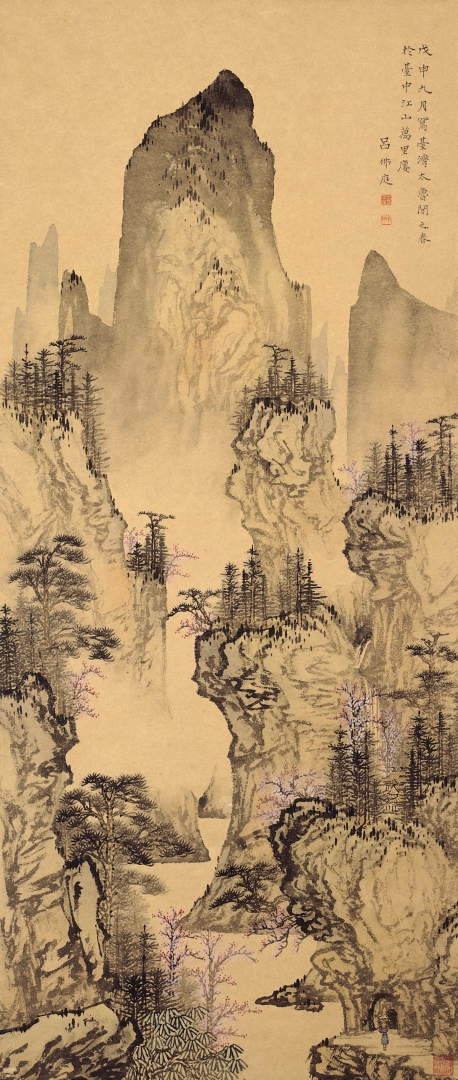

Downstairs we came across some magnificent ceramics (we had seen a brother of one particularly snooty glazed mandarin in the Silk Road exhibition at the British Museum), old bronze bells and vessels, figures of the sun god and moon goddess, millennia-old carved oracle bones and an exhibit on the interesting Chinese Cultural Chests put together and exported by the Taiwanese government in response to the colossal vandalism of the Cultural Revolution across the strait. Painted landscapes of the Taroko Gorge make me excited for tomorrow’s trip there. The gift shop had a range of interesting art suggesting that the wider permanent collection, when it reopens, will be absolutely spectacular to see.

We headed north through the botanical gardens, full of moorhens, wisteria and tall slim palm-trees (with the cold and rain we’re getting it’s easy to forget that Taiwan is literally a tropical country). Three separate locals were taking artistic shots of flowers in puddles outside the Qing-era Guest House of Imperial Envoys, where huge painted guardians and courtiers gaze down from the beautifully carved eaves. A sign in one bed of bright flowers proclaimed “Today, I am the best !” We navigated (badly; Citymapper works here, but really struggles with the right exits from metro stations) to the main station for a rushed meal of FamilyMart konbini food (service station food, basically, but a bit better quality) and a big, clean if slightly old-fashioned train to Hualien.

I napped through Taipei’s outskirts and woke in a landscape of paddy fields and drainage channels. Alongside the track we saw parked orange locomotives with white moustaches, and very serious-looking level crossing warnings made of girderwork striped in black and international orange. The landscape, cloud-shrouded hills ever in the background, was full of paddy-fields and infinite little variations on the “box of small flats” structure, often lower and sparser among the bigger paddies but never below two storeys and never entirely out of sight. Towns rose and fell past the train, with the odd ornate red-pillared temple or hazy industrial facility mysterious in the grey rain. Further south we came to hilly country with ear-popping tunnels and loads of cement works. Pale grey riverbeds, mostly dry, cut into the rising cliffs to the right, and to the left rolled the steel-blue ocean.

We hit Hualien’s big modern station at dusk and got a quick taxi to our B&B on the coast (the very nice lady at the desk showed us how to navigate town and gave us slices of welcome pudding) before heading out to its night market. This was a significantly more established, somewhat more haggard setup than in Taipei (Hualien’s tourism scene depends heavily on the Taroko Gorge, which is still recovering from a big earthquake last year): there’s more of a “carny” feeling to the plastic tat stalls, a lot more barkers trying to bring in custom and a lot more closed stalls (it was also, to be fair, a cold rainy Sunday night). Local specialties included a chicken breast filled with bacon and cheese and deep fried, sweetcorn tormented over a slow flame with barbecue sauce for 20 minutes, a “coffin sandwich” which is a sort of club eggy bread full of Szechuan-peppered beef, an easy-mode version of the stinky tofu that had been so distinctive in Taipei, a coconut that a friendly fellow (indigenous Taiwanese, I think) chopped open with a machete and added a straw, just like in Sri Lanka, a stick of bamboo filled with sticky white rice, and yet more excellent variants on Taiwanese tea plus a sweet local rice wine with a serious kick to it. Comfortably full, we wandered back to the B&B along the shoreline, listening to the horns of distant ships and the endlessly crashing Pacific.

Taiwan 2025

Jiufen and Houtong / Taipei Museums / Taroko Gorge / National Palace, Lungshan Temple / A Brief Interlude / CKS Memorial and Maokong / Dihua Street, Taipei 101 / Anping District and Forts of Tainan / Tainan History / Fenqihu / Alishan

* I really need to read some other sources on SYS; the only one I’ve had is Jung Chang’s portrayal of him in her latest, which is not so much a character assassination as a character cluster-bombing.

It all looks really interesting…. hut did it ever stop raining??????

Best to you both

Sue x

>