A BRIEF INTERLUDE ON THE HISTORY OF TALLINN from which, at a glance, the most impressive thing about the place is that it’s independent at all. The Estonian state in its modern incarnation has existed for less than 45 years, in two non-consecutive periods, and already has two independence days, both celebrating getting away from Russia (the first in February, celebrating the 1918 independence; the second, in August, celebrating the 1991 independence, in a “for real this time” sort of way.)

Tallinn has been around for a long time, as raiders’ outpost, Hanseatic trading port, fortified naval base, and eventually capital of its own country. But it is mainly a history of being batted about, invaded and occupied by the dominant regional power of the time, and there have been a lot of those in the Baltic. The extensive and wonderful medieval city walls surrounding the Old Town, the enormous trace italienne fortifications surrounding them, the monstrous coastal ex-fortress (“Patarei” means “battery”) and the fancy seaplane hangars are all parts of the Baltic power game.

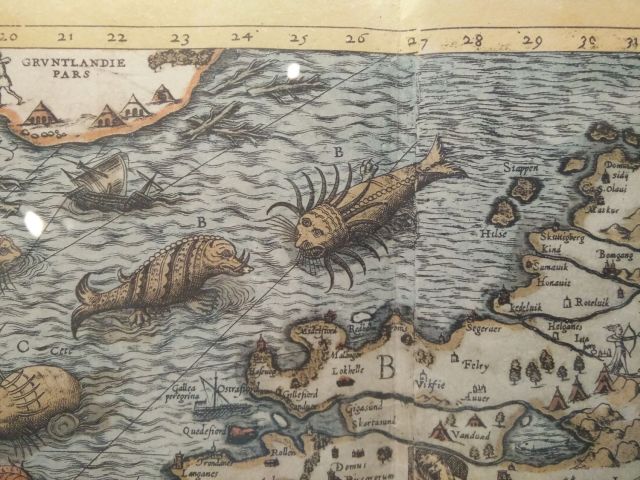

Estonians are related ethnically and linguistically to Finns (and thus, going a very long way back, to Hungarians) – the ancient Estonians existed as one of the many seafaring, sometimes-trading sometimes-piratical groups operating in the Baltic through the Dark Ages, which we English inelegantly give the catch-all name “Vikings”. They were one of the last pagan groups in the Baltic, principally because neither the Catholics on one side nor the Orthodox on the other wanted to set off a holy war with the other, and fought variously with Danes, Swedes and the Republic of Novgorod (the northern proto-Russian state which was later subsumed into the Grand Duchy of Moscow) as well as ignoring and, er, possibly eating various luckless Catholic missionaries from the German states. They built hill forts and stone castles, including the basis for the later Toompea Castle on the Tallinn citadel. In the 13th century the Christianised Danes, sick of Estonian raiders, allied with the Teutonic Order to launch a Northern Crusade into the area, slaughtering the loosely confederated pagan tribes, wrecking their hill forts and eventually (in the face of some violent revolts) establishing a state called Livonia, run by a Christian knightly order called the Livonian Order, or Sword Brethren.

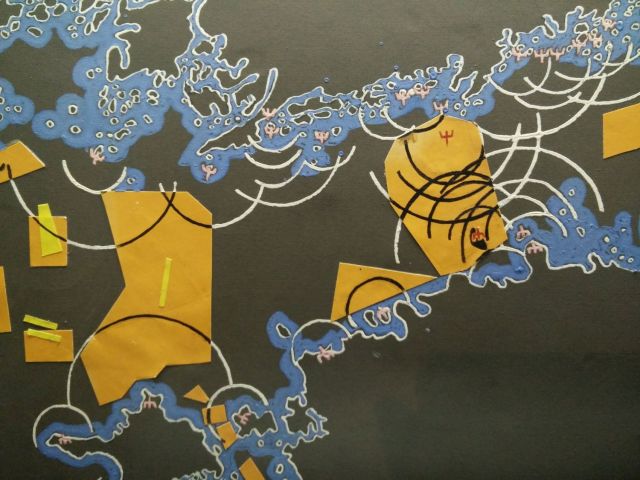

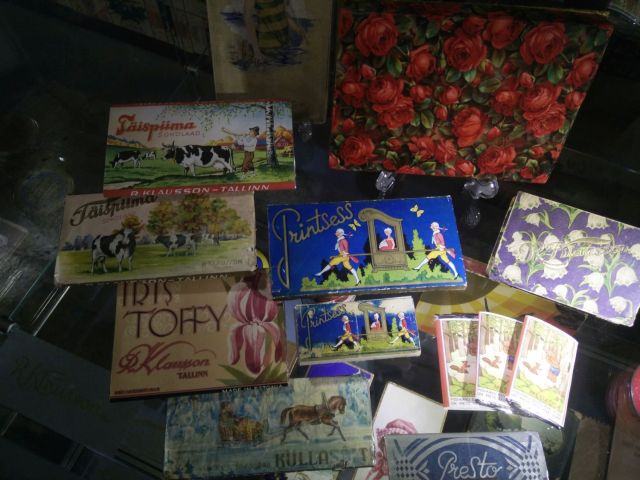

A variety of horrible wars – Sweden, Denmark, Muscovy and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth being the main players – swept over Livonia for the next three centuries, but Tallinn itself mostly did fine. Known as Reval at the time, it had become part of the Hanseatic League, an immensely influential semi-formal association of merchant towns, which ran most trade in northern Europe from the thirteenth to the eighteenth century. Serving as a natural point for trade between Muscovy and everywhere else, Reval was coining it, and this period was when the town hall and the main late-medieval fortifications, including Fat Margaret and the Kiek in de Kök, were built – both protecting the city’s wealth, and displaying how rich they were to be able to afford this sort of martial bling. Fancy walls and Hansa status weren’t an invincible defence, however, and with the rest of Estonia Tallinn mostly-voluntarily came under the power of Sweden in 1561. The Swedes, then an up-and-coming power who cemented their Baltic pre-eminence in the apocalyptic Thirty Years War of 1618-1648, considered Reval an excellent base to bottle up the Russians, and invested a staggering amount of money into defensive upgrades – the enormous bastions, redoubts and ravelins that surround the medieval walls to this day.

Sweden’s Baltic dominance and ownership of Tallinn lasted until the Great Northern War (1700-1721), when Peter the Great of Russia kicked the shit out of the Swedes and took all of Estonia as war booty. (True to form, Britain involved itself on the weaker side for postwar concessions, switched sides halfway through and generally enjoyed watching everyone get wrecked.) The improved fortifications were never tested – the horrific plague outbreak that ravaged the Baltic during that war reached Tallinn in 1710, just before a Russian army did, and after losing two thirds of their population to the plague the survivors collectively went “sod this, not worth it” and opened the door to Ivan.

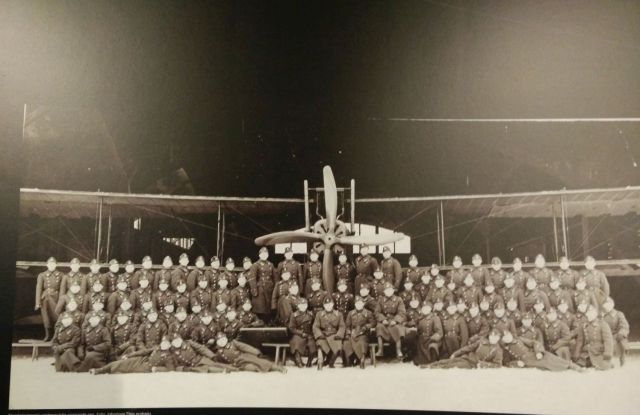

Tallinn was part of the Russian Empire for the next two centuries, and went through the same general developmental upheaval as the rest of Europe, but retained its prosperous trade, its medieval old town and its German mercantile-urban elite, the last only leaving in the 1890s. British and French ships blockaded it during the Crimean War, but didn’t attack. In the run-up to the Great War, it was a key component of the enormous Russian effort to block off St Petersburg from the sea with coastal fortresses in Estonia and Finland, and Royal Navy submarine squadrons used the port for raids on iron ore convoys from Sweden to Germany; and, during the utter chaos of the Russian civil war, the Eestis took advantage of everything falling apart to declare an independent state, with its own democratic government and adorable little excuse for a military.

Russia invaded again in the 40s, twice: the first time, in the aftermath of Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, they annexed the Baltic states, abducted the existing governments, military, police etc and deported them to Siberia in cattle cars to die, set up puppet governments claiming to be “popular fronts” and legitimised them through rigged elections, shot anyone who resisted, and generally made such a horror of themselves that when the Nazis attacked in ’41 they were welcomed as liberators. The Nazis, of course, did their usual thing with Jews (not that there were many in Estonia by that point) then, as the Eastern Front moved so decisively westward in 1944, the Soviets returned, kicked the Nazis out and killed or deported everyone who had cooperated with them and anyone else they found slightly threatening. They again installed a puppet government as the Estonian Soviet Socialist Republic, then carried on doing their general repression thing until the mid 50s, breaking resistance through mass deportations, conscripting the young men for forced labour, sending dissenters and people with money to the gulag etc – all of which was partially reversed with the Khrushchev thaw. Then, when the USSR collapsed, Eesti got independence again in 1991, and threw in with the EU and NATO as quickly and enthusiastically as it could; you spend Euros in the shops now, and there are semi-permanent NATO deployments there. I didn’t get any impression of tension while there – Tallinn has a huge Russian-speaking minority, most tourists there are Russian, and if anything we got treated better having a Russian friend than we did just speaking English – but the country is clearly on Putin’s shopping list, and sabres are being rattled on both sides of the border.

Tallinn 2015

Old Town and Toompea – Linnahall, Patarei Prison, Seaplane Museum – A Brief Interlude on the History of Tallinn – St Olaf’s, Fat Margaret, Old Hansa