I’m (finishing) writing and uploading all this in 2022 but I was actually in Petersburg in 2015. You can see the whole series in a tag here, or start at the Estonian border here.

In its heyday, Kronstadt was an unbelievably strong fortress. Successive Tsars from Peter the Great onwards went to enormous lengths to protect Petersburg with a network of island fortresses, coastal batteries, minefields, artificial reefs and sundry ship-killers, centred around the fortified island of Kronstadt (translates basically to “crown-town”). The current Tsar, Vladimir Putin, has outdone all his predecessors by also blocking off the sea, and a gigantic flood barrier surmounted by a motorway was recently completed, protecting Petersburg from storm surges, which these days present more of a threat than Swedish men o’war.

An ill-maintained coastal road took us to our first destination, Fort Krasnaya Gorka (Redhill, essentially). There were little trios of red-white-blue streamers hanging from trees, combining to form a Russian tricolour, but for some the blue had broken off and instead made a Polish flag. The fort is abandoned and completely overgrown now, still a tourist destination but not run as a proper museum, for lack of money; it’s not even signed, and it was through a combination of Google Maps and dead reckoning we negotiated an uncomfortably cobbled track and eventually a sandy path through the duneland.

Among the fortifications I found a lightbulb the size of a newborn baby; then a 10cm railway gun, on a rotating turret with folded stabilisers; and then a 30.5cm railway gun, a gigantic olive-drab piece of steel mounted on a carriage the size of a house stabbing up at the grey sky as though giving the middle finger to God. Past the gun are lines of masonry emplacements in varied states of collapse, some so intact we could crawl through their tunnels (lined with curious pipework I eventually recognised as a fire suppression system), some indistinguishable from the dunes around them. During the Revolution, the soldiers here got cold feet about the whole Bolshevik thing, and Lenin sent Trotsky to deal with it. Trotsky promised safe conduct to the soldiers if they surrendered peacefully; they did, and he machinegunned every man jack of them. Classic Trotsky.

Driving across the barrage, over and then briefly under the water, we came to Fort Konstantin, which was once an arrowhead-shaped island battery but is now just a weird protuberance off the motorway. Konstantin is much better preserved than Krasnaya Gorka, if still disarmed, and we echoed ghost noises down its dark, dripping halls; I followed the tracks of a shell trolley, from the base of the gun barbette to a shell hoist down into the bowels of the fort, and the rails taking it to the magazine chambers, under metres of brick and earth. Then we hopped on a little boat – blankets provided, and needed, even in midsummer – taking us to Fort Alexander.

Brosencrantz: which is basically a russian Fort Boyard

Demsale: do they host a game show there?

Brosencrantz: no, but they used to have a plague laboratory

Demsale: ok but fort boyard had a game show

Brosencrantz: I know

Brosencrantz: this is Russia

Brosencrantz: you don’t get dwarfs or tigers

Brosencrantz: you get plague

Fort Boyardski Alexander is a bean-shaped triple-decker gun fort; the dark red brick and stone of its walls only add to the impression of a gigantic battle kidney. Its jetty (where the renal artery would be) had a wonderful old wrought-iron crane, mooring bollards made from real 24-pdrs, and washing lines carrying strips of fabric (“What are these here for?” “To keep away oligarchs with helicopters.”) Inside it’s dark and chilly, with excellent cast-iron stairs. I didn’t understand the tour, which was all Russian, but appreciated the architecture and the location, and got choice bits translated for me – “the brickwork is of unusually high quality for a Russian fort because the workers here were hired men, not slaves.”

Finally, we came to Kotlin Island, and Kronstadt itself. Even by the very high local standards, it has some interestingly hideous history. In 1917 the sailors there were some of the first proper revolutionaries; they mutinied, murdered their officers and quickly became known as the reddest of the Reds. But in 1921, after four years of insane Bolshevik mismanagement and tyranny, they were starting to have their doubts about Lenin, and issued a manifesto saying they wanted the Soviets to be more democratic and accountable, run some elections soon and maybe let peasants own their own cows. Lenin, predictably, took this poorly, and decided that sending unsupported infantry across a frozen sea to mount a frontal assault against a massive fortress island full of battleships and highly motivated sailors sounded like a right laugh. Twelve days of insane slaughter and over ten thousand deaths later, the Bolsheviks had the island. Some of the sailors escaped to Finland; most of them died defending Kronstadt, or were captured and shot or sent to Siberia. It was something of a watershed moment for the Soviets: firstly, because the Kronstadt sailors were as Red as it came, the fact that even they thought shit was fucked forced Lenin and co to reevaluate War Communism and begin the New Economic Policy; secondly, it set all future Bolshevik policy for dealing with criticism or opposition (ie: instant and overwhelming violence).

The town itself is very quiet and peaceful. Many of the buildings, a mix of old red brick (some still pock-marked with bullet holes) and mid-century tower blocks, are abandoned now, their fortunes waning with Russia’s always-a-bit-uncertain status as a naval power. What’s left over doesn’t seem to be having much success trading on its history: a dead factory canteen still bearing Soviet names and iconography, shop windows with tacky chubby-cheeked dolls in military uniforms, a scatter of statues busts of bewhiskered gents who’d met the fairly low bar of being acclaimed as a Russian naval hero.

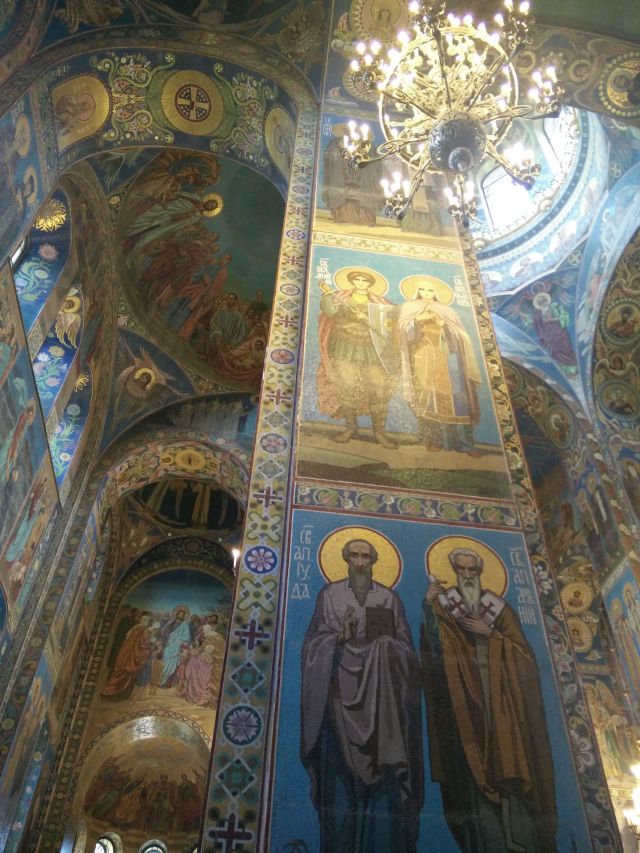

We had cheap tea and pastries at a little cafe, then moved on to the Sailor’s Cathedral, possibly the single most blinged-out and beautiful piece of Orthodoxy I’ve ever seen (and that is saying a lot). Its light fittings were fixed to huge suspended metal rings echoing the domes far above them; one of its gates was covered in black-and-orange striped ribbons. Outside, a mad old man with a Tolstoy beard talked to the pigeons among the swirl of Russian tourists. The square is paved with white and black stone, and it’s only from aerial photographs (or, perhaps, the top of the cathedral) that you can make out that the black forms the shape of a stylised anchor, hundreds of metres long.

On the square is Admiral Makarov, another big Russian naval figure (the first chap to sink another ship with a torpedo; he died along with the painter Vereshchagin when his flagship, the battleship Petropavlovsk, hit a mine off Port Arthur). The grid of military canals originally carved into Kotlin are no longer suited for fitting out warships, and many are dry now, forming lovely valley parks.

The navy is still there, but they’re down to one half of one quay (razorwired off and heavily guarded) : a clutch of mean-looking dark grey missile boats, an icebreaker, a big, graceful white survey ship that looked as though it belonged to another age, a single diesel submarine. A cruise ship churned by past the breakwater, the lighthouses and pillboxes around its ankles only underlining how impossibly big it was.

Kronstadt feels a good place to end on. Its history is a struggle, of human will against elements, geography, and human will; war and suffering, politics and bloodshed, engineering, sacrifice and cruelty on an unbelievable scale. It is peaceful now, and much of its beauty remains; it is decrepit, but it is proud, and remembers better days. But peace has never shaped it the same way as war has, and there is always another war to come.

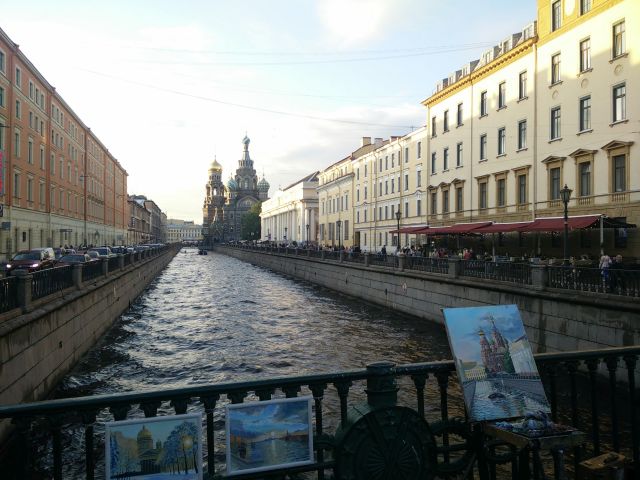

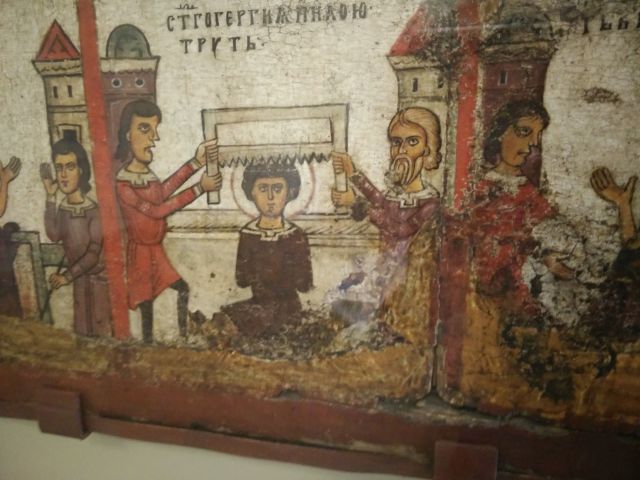

Border crossing, monuments by night – Downtown Petersburg, St Isaac’s Cathedral, Peter’s Aquatoria – Peter & Paul Fortress, Artillery Museum – Nevsky Prospekt, Saviour on Spilled Blood, The Russian Museum – Central Naval Museum, Icebreaker Krasin – Neva bridges – Krasnaya Gorka, Kronstadt