The tides were not with the “Park & Float”, so I took the bus down from Penryn (clean, modern, on time, reasonably priced and everyone’s wearing a mask. Also – so far the single positive from this pandemic – everything takes contactless.) It passed the almost Genoese-looking church of St Mary the Immaculate and terminated at “The Moor”, Falmouth’s main square, all stout Victorian municipal architecture, cheery bunting and the cry of the gulls.

Finding a large pasty for breakfast was no trouble; determining which of the many different boats from the pier I should be taking to St Mawes only slightly more (another piergoer gave me a tab from his ticket which knocked 50p off the return.) The wind was up, blowing black Cornish flags hard across a low, leaden sky, and the “Duchess of Cornwall” was the first boat sailing that day. We threaded through the great flocks of parked yachts in the Carrick Roads, past a huge floating crane and the Argus.

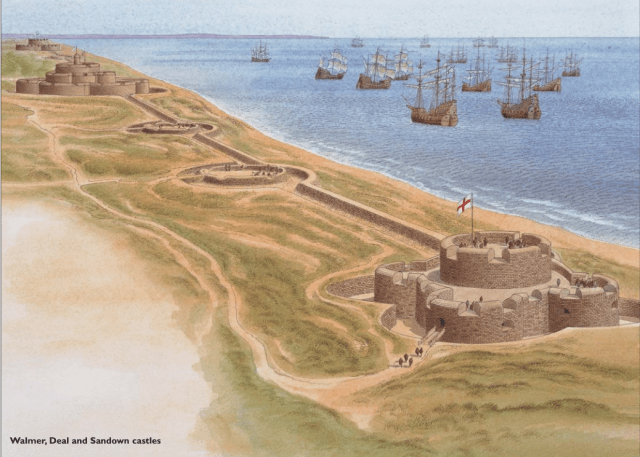

I’ll post separately about St Mawes, that most beautiful and perfect of all Device Forts, but it was a cracking time, and a great pleasure to bring my model right up to the real thing.

Back in Falmouth (the ferry is very regular; children were crablining at the harbour) I refuelled and headed to the National Maritime Museum (Cornwall), a huge weathered-wood structure that recalled the Vasa’s housing in Stockholm. Rather than one galleon, it was absolutely chock full of smaller boats – everything from racing hydroplanes to ornate Maltese dghaisas, preserved fishing boats and a tiny dinghy called “Optimist”. The accompanying galleries deftly told stories of maritime history in general and Falmouth’s in particular. After the Restoration, the town picked up the status of Cornwall’s most important port from Penryn (much to Penryn’s dismay). It was known from late 17th to the early 19th century as the home of “packet ships”, fast mail boats carrying small high-value targets. Falmouth’s location as the first good harbour in the British Isles from the southwest, and a reliable place to send off fast boats rather than worry about the changeable winds up and down the Channel (not to mention hostile warships and pirates) brought it considerable prosperity. In the 1830s, steamboats (and prolonged peace with France) destroyed these natural advantages and Falmouth’s port instead handled holidaymakers, Cornish emigrants to Australia and the New World, and warships, including acting as the setting-off point for the demented St Nazaire raid of 1942.

Leaving the museum, a stomp uphill took me into the sudden sunny calm of the west side of the peninsula, and along to Pendennis Castle. Pendennis is one of those marvellous old accretions of defensive architecture, with a Tudor core of similar size and vintage (though very different layout) to St Mawes sitting inside a giant 18th century bastion fort*, with Napoleonic barrack blocks, and that rare sight, Armstrong RMLs on classic looking fortress carriages.

The Tudor gun-fort itself has its original portcullis and the guide pointed out all the modern conveniences of value to the discerning mid-16th century king, like vents for powder smoke and internal loopholes for defence in depth. He also explained that the big square cutout below Henry VIII’s stone coat of arms was for the castle’s warden to put their own coat of arms in wood – a design feature I’d seen on loads of Device Forts but not made sense of before.

The fort’s perimeter has all sorts of wonderful pieces – a Victorian disappearing gun (the mounting wasn’t quite right but got the point across) and a fully equipped WW2 rangefinding station – the metal platforms for the depression rangefinders I’d seen in Gibraltar at last made sense. By using the rangefinder’s handles to aim its telescope at a target, the system would (through careful gearing) put a pointer on the exact location on a large map, giving you a ready-made firing solution. The Cornish translations of all the signs were charming – I now know how to say “dangerous explosives” and “little smasher” in Cornish.

I took a circuit of the great sloping walls and descended to the southernmost point to visit the blockhouse “Little Dennis”, another Henry VIII survivor and one of the best preserved of his blockhouses (less substantial than a proper castle, more permanent than an earthwork battery; think a sort of 16th century pillbox) which now mostly only exist as floor plans. I sat in the main gunport for a while, enjoying the view across the Carrick Roads and the crazed strata of volcanic rock full of tidepools. As I headed back up for a bus home, the clouds, sun and rain conspired for a moment to pick out the blockhouse in glorious golden with a flash of rainbow behind it.

* Falmouth is one of a tiny handful of places in the British Isles with a proper star fort (of which I’ve seen Tilbury, Landguard, Fort George, Berwick-upon-Tweed and the barely-recognisable shambles around Sheerness.)

Out to Penryn – St Mawes and Falmouth – St Austell and Plymouth – The Forts of Staddon Heights – Drake’s Island and Saltash – Totnes and Exeter