This series was originally jointly on my blog and Philip Reeve’s, but his has been overrun with malware so all four posts are now on my own site: Part 1 Part 2 Part 3

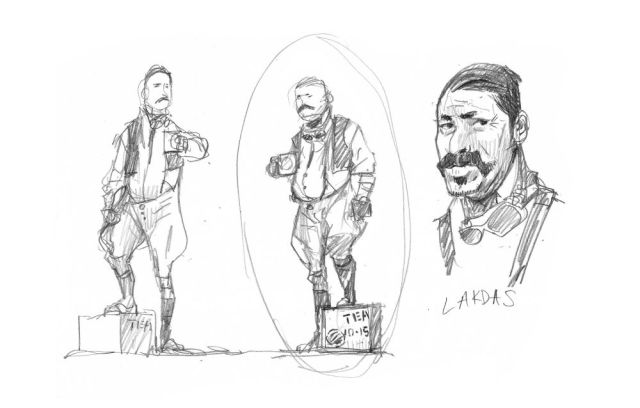

T is for Rob Turpin

Early on in the development of the IWOME, it had more of an artbook-y feel: big, fancy full-colour works taking up whole pages at a time, with the relevant text on the opposing page and any empty space filled by fancy cogwheels (which ended up on the cover.) We wondered if we could make it feel more of a technical, encyclopaedic sort of thing, the sort of book which says “refer to Fig. 2a”, by adding more, smaller illustrations – perhaps little black and white ones…?

To which Jamie, the Scholastic design manager, said “Ah! I know just the chap!” Rob Turpin is an illustrator and designer from Yorkshire who has been living and working in London for the last twenty years. Mainly working in science fiction and fantasy, Rob has a love for spaceships, robots, imaginary places, and the colour orange…

Rob’s lovely little cities, full of detail and personality, crowd the book and are all laid out in the endpapers. In particular, he’s taken on all the more bizarre experimental cities, like Panjandrum, Vyborg, Borsanski-Novi and Havercroft. Probably my favourite of these is the Nuevo-Mayan piranha town. We originally envisioned these as smaller than the first version he sent in, only about the size of houseboats, but the one he sent was so lovely we had to keep it in anyway, with a little squadron of smaller friends. And, absolute gentleman that Rob is, when I said it was my favourite, he only went and sent me the original art…

Rob is thisnorthernboy on a lot of sites: Twitter, Instagram, WordPress, and ellipress where you can buy prints of his work. Give them all a look!

U is for Uncertainty, or Unsolved Mysteries – it’s all one.

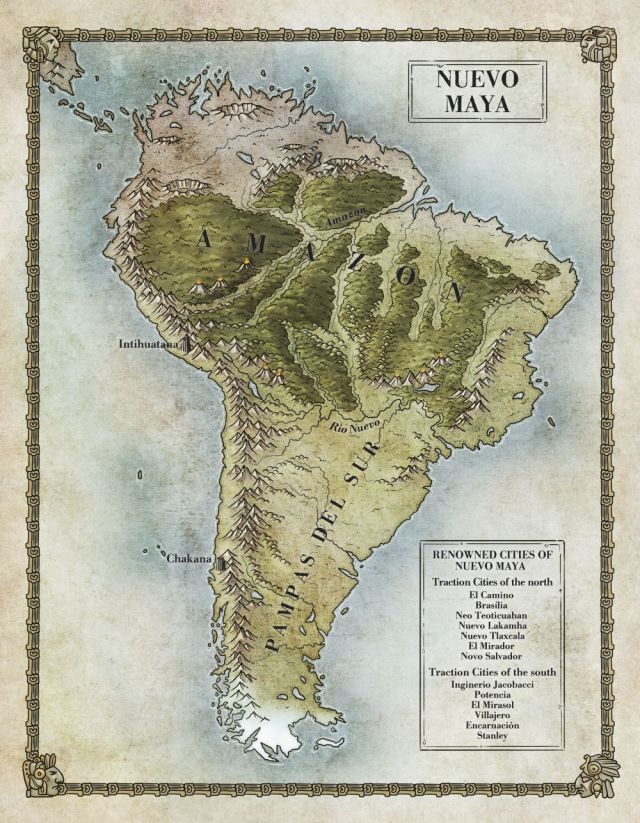

The IWOME answers a lot of questions. Readers will come away knowing how London got from the end of Scrivener’s Moon to the start of Mortal Engines, how Tractionism spread to India, which was the largest moving city ever built, what on earth is actually going on down in Australia, and who originally used Nuevo-Mayan Battle Frisbees. They will also have a much better idea of the geography of parts of the world and how much the Sixty Minute War really reshaped things, which has been a source of great speculation and interest in the fan community.

But it doesn’t answer all of them. This isn’t an exhaustive encyclopaedia or comprehensive atlas; we have no interest in naming every Traction City ever built and categorising them all. The book leaves a great deal up to the reader’s interpretation and imagination; it’s a history as seen by people inside the world, which is still full of mystery and uncertainty. Hopefully, we’ve left a world that feels wider, rather than narrower.

V is for Philip Varbanov

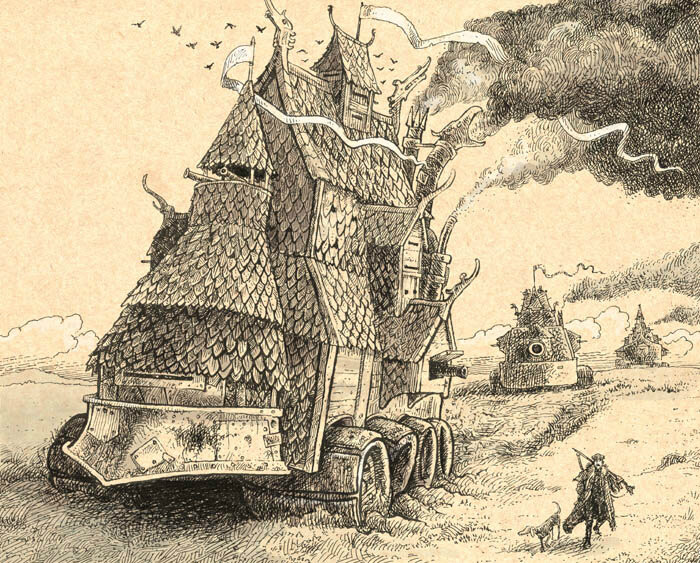

As mentioned in Exploded Diagrams in the first blog, something we were anxious to include from the very beginning was artwork which captured both the scale and the detail of a Traction City. And for that, Philip Varbanov’s work exceeded all our hopes.

Philip is a concept artist and illustrator with a background in fine art and graphic design. He’s based in Sofia, Bulgaria, and works in the entertainment industry, specialising in environment art and production drawings. He illustrated the “Evolution of London” series at the start of the book, as well as several helpful cutaways of traction cities, an illustration of the Municipal Darwinist food chain and a stunning Jenny Haniver.

Philip’s works are striking for their great attention to realistic-looking mechanical detail. His drawing of Fever’s London on pages 10-11 is a masterpiece – we were worried it wouldn’t be possible to get central London, Nonesuch House (which is well away from the centre, on the edges) and the Orbital Moatway (which is far off on the horizon) all into the same drawing satisfactorily, but Philip used space and perspective so cleverly the whole thing just works.

He tweets as @moobsius, and you can see his fantastic portfolio at https://philip-v.com/

W is for David Wyatt

Chances are if you’re a fan of Philip Reeve’s worlds you’ll already be familiar with the works of David Wyatt. He’s responsible for the charming black-and-white illustrations of the Larklight series and, closer to home, a series of Mortal Engines and Fever Crumb covers (along with the Haunted Sky comic-that-never-was.) His covers are exactly how I imagined the world of Mortal Engines as a little boy, and the IWOME simply wouldn’t have felt right without him involved.

Chances are if you’re a fan of Philip Reeve’s worlds you’ll already be familiar with the works of David Wyatt. He’s responsible for the charming black-and-white illustrations of the Larklight series and, closer to home, a series of Mortal Engines and Fever Crumb covers (along with the Haunted Sky comic-that-never-was.) His covers are exactly how I imagined the world of Mortal Engines as a little boy, and the IWOME simply wouldn’t have felt right without him involved.

David’s huge full-page illustrations are scattered through the IWOME. All his works have an incredible sense of atmosphere: contrast the rain-slick, overcast landing pad of the 13th Floor Elevator with his light, airy Brighton, or the calm of his Zoffany-like art gallery with the oppressive, chaotic Battle of Three Dry Ships, where a three-tiered London grinds implacably into view over a blood-red battlefield. I also adore his Nuevo-Mayan traction city chase, which is like the cover of a Mortal Engines book that never happened – it’s so close to what I had in mind when writing the brief it’s spooky.

David is a prolific illustrator (I hadn’t realised quite how prolific until, looking at his portfolio, I found half the books of my childhood were in his covers – everything from The Hobbit to The Amazing Maurice and his Educated Rodents), and recently won the Blue Peter Book Award for The Legend of Podkin One-Ear alongside Kieran Larwood. Like Philip Reeve, he lives on Dartmoor, and you can see evidence of its mossy hillocks, windswept tors and curly, spooky old trees in his art here. More of his IWOME art (among many wonderful other things) can be found on his blog here.

X is for Xanne-Sandansky

…one of the many, many Traction Cities mentioned in the Quartet, but which never got its own entry in the IWOME. I’d love to come back to it – there are plenty of ideas for cities which we never quite got round to.

Xanne-Sandansky is best known in the IWOME as the eater of Borsanski-Novi, a catch so crammed with spare parts and useful machined goods that its Gut bosses had a spring in their step for months thereafter.

Y is for whY can’t I think of anything for the letter Y?

It’s a copout. But I really can’t. Suggestions in the comments section, please…

And finally, Z is for Amir Zand.

Although he’s last in the alphabet, Amir Zand was one of the first artists involved in the IWOME. Amir is an Iranian illustrator and concept artist, specialising in cover art and promotional illustration. He’s been featured in numerous magazines and books, including Spectrum 25: The Best in Contemporary Fantastic Art, and has illustrated more than 35 book covers.

Although he’s last in the alphabet, Amir Zand was one of the first artists involved in the IWOME. Amir is an Iranian illustrator and concept artist, specialising in cover art and promotional illustration. He’s been featured in numerous magazines and books, including Spectrum 25: The Best in Contemporary Fantastic Art, and has illustrated more than 35 book covers.

Amir contributed all sorts of works to the IWOME, providing a marvellous set of mutant creatures (his Maydan Angels look rather a lot like shoebills, which are easily the most malevolent-looking birds in the world) and a lot of static settlements as well as a wonderful variety of cities (his Juggernautpur, continuing the “person in front of Traction City” theme of the Ian McQue covers, also looks like the cover of a book which hasn’t been written yet.) Amir’s works are all incredibly evocative: you can feel the chill of his winter-dawn Kometsvansen, the heat of the sun on his gleaming Zagwan city, and the aching stillness of his wreck of Motoropolis, lit from below by scavenger’s spotlights in the purple night. One of my favourites is his Panzerstadt-Bayreuth, a huge, intimidating silhouette wreathed in smoke and scattered with lights, and you can get a sense of how Londoners must have when they saw it bear down on them in Mortal Engines.

More about Amir, including an excellent portfolio, can be found at his website http://amirzandartist.com, and he also tweets as @amirzandartist.

Pictures in order: Piranha suburb, Railhead postcards and Kom Ombo, by Rob Turpin; Sky-train, by Philip Reeve (originally for the Traction Codex); detail of pre-Traction London and Diagram of Municipal Darwinism , by Philip Varbanov; Airhaven and Nuevo Maya, by David Wyatt; Traction City, by Philip Reeve; Arkangel, detail of Panzerstadt-Bayreuth, and Tunbridge Wheels, by Amir Zand.

A problem with setting things in the future that refer back to the present is that the present won’t stand still, and episodes of Black Mirror keep coming true. Most of the stuff being dug up in the world of Mortal Engines is old tech right now. Fever Crumb found herself standing on a floor tiled with iPods in Scrivener’s Moon, which is about all they’re useful for now. When Tom first found a CD in Mortal Engines, they were common, but here in 2018 they’re now less popular than vinyl, for some reason. How long until they’ll need explaining to young readers, as if he’d found a VHS or a 5″ floppy disc? (Perhaps this is why the film seems to have replaced it with a toaster…)

A problem with setting things in the future that refer back to the present is that the present won’t stand still, and episodes of Black Mirror keep coming true. Most of the stuff being dug up in the world of Mortal Engines is old tech right now. Fever Crumb found herself standing on a floor tiled with iPods in Scrivener’s Moon, which is about all they’re useful for now. When Tom first found a CD in Mortal Engines, they were common, but here in 2018 they’re now less popular than vinyl, for some reason. How long until they’ll need explaining to young readers, as if he’d found a VHS or a 5″ floppy disc? (Perhaps this is why the film seems to have replaced it with a toaster…)

We owe the Historians of the WoME a great deal, and gave them Puerto Angeles for their trouble, a cheerful historian party city where the museums and the samba clubs are both 24/7.

We owe the Historians of the WoME a great deal, and gave them Puerto Angeles for their trouble, a cheerful historian party city where the museums and the samba clubs are both 24/7.